From Blobs to Blockchain: Inside the New Takedown-Resistant Skimmer Tricks

October 10th, 2025 | By Gareth Bowker | 18 min read

Attackers are constantly finding new ways to evade defenders' protections. Whether it's through obfuscating their code, compromising plugins, poisoning content delivery networks (CDNs), or through supply chain compromises, these attacks continually plague e-commerce websites.

Now, there's a new twist: the latest Magecart-style campaign, analyzed by our researchers, was discovered to be stashing its payload inside blockchain smart contracts and using novel ways to bypass Content Security Policy (CSP). Jscrambler's security research team has been tracking this attack since February 2025. Below, we detail some of the latest methods used by attackers, along with guidance on how to protect your business.

Discovery

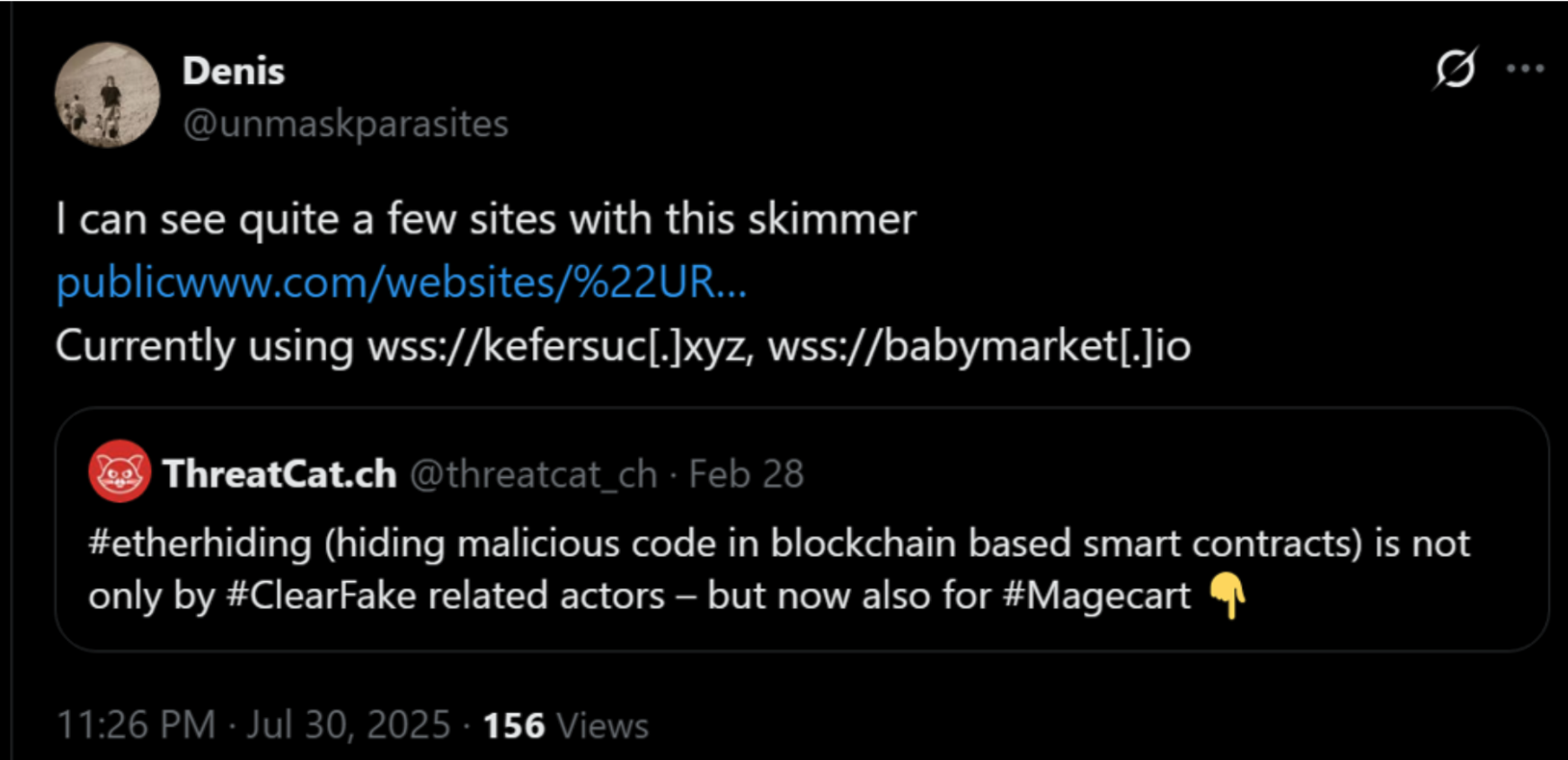

Jscrambler tracks numerous skimming campaigns across the Internet as part of our ongoing effort to keep the Magecart classification in Webpage Integrity current. Identifying and monitoring this campaign all began with this post on X:

A few months later, a related post appeared:

Clicking on the link, the search string used by the researcher stood out to us:

"URL['revo'+'keObj'+'ectU'+'RL']"This was a simple obfuscation of revokeObjectURL(), a JavaScript function that the attackers were chopping up in this manner to try to hide their tracks. We searched for sites containing this specific string and quickly found dozens of them. Upon closer examination, they all contained web skimmers designed to siphon off cardholder data. Nothing new has been observed so far; however, as Jscrambler's research team continued to examine the attack code, they discovered a couple of new techniques that had not been observed before.

First, one of the pieces of the attack was stored in a blockchain smart contract, and second, it employed some interesting techniques using "blobs" that allowed the attack code to evade most CSP configurations currently in use.

How does it work?

As with most campaigns these days, the attack operates in several stages and appears to be a toolkit, allowing attackers to tailor the attack to the specific website they've compromised. The first stage, the initial loader, is placed on the compromised website by the attacker. While we don't know exactly how the attackers carried out the initial compromise, it's often due to unpatched vulnerabilities or misconfigurations, such as default/weak passwords on the website or server.

Attackers use multiple stages for several reasons. First, they don't know how long they'll have access to the compromised host, and may not have time to tailor an attack script before they lose access. By linking out to a third-party website over which they have complete control, they can gain a foothold and tailor their malware later. Second, adding a small loader script rather than a full attack script makes it less likely that someone casually reviewing the code will detect that something unusual is going on. The loader is often made to appear innocuous, for example, by referencing well-known services like Google Tag Manager.

Let's delve into one of the infections we've seen now.

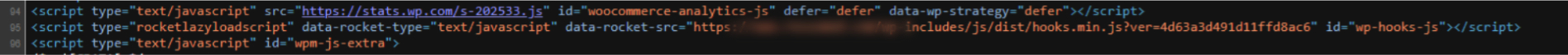

Stage 1: Loader

We noticed several variations to the first-stage loader, depending on exactly what technology stack the victim website was using. As we examined these different loaders, we discovered some interesting elements to the first stage of this attack for some victims:

First, the tiny bootstrap snippet is lightly obfuscated. In some instances with a twist - instead of using the usual MIME type of "text/javascript", which tells the web browser that the snippet is JavaScript code and to execute it, this loader instead uses a fake MIME type (rocketlazyloadscript), which is later rewritten into active JavaScript on the client-side by a legitimate WordPress plugin, WP Rocket.

This technique of changing the MIME type is used to attempt to conceal JavaScript code from static analysis tools that scan websites for it. It relies on a legitimate behaviour in the WP Rocket plugin, which is meant to optimise page load times by delaying scripts from loading until after a page has been rendered in the web browser.

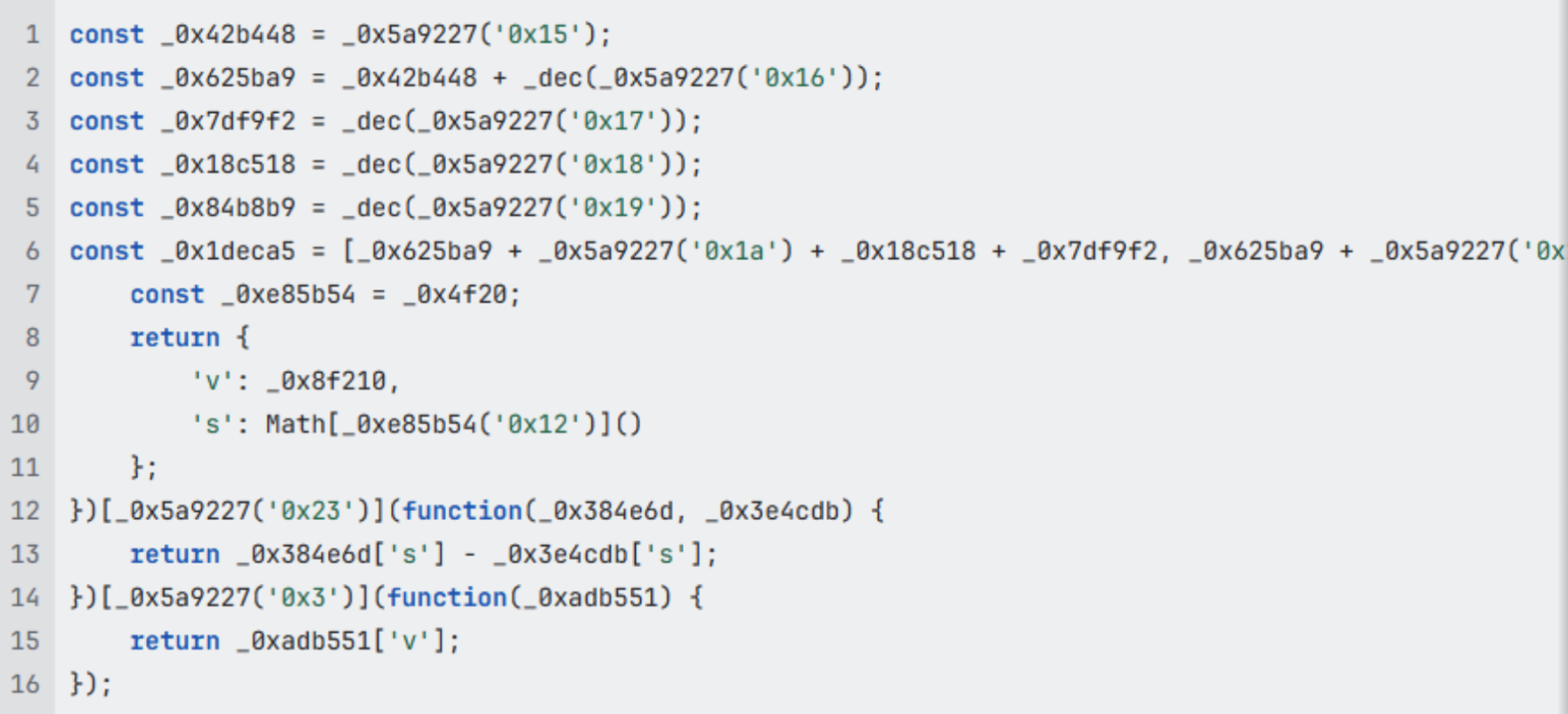

Second, this code unusually relies on JavaScript "blobs" (Binary Large OBject) - ephemeral, in-memory JavaScript objects that exist only as long as the page is loaded. Usually, these objects are legitimately used for generating dynamic content, such as loading images or video without writing them to disk, but in this case, the attackers are using them to keep the attack code out of the webpage's DOM. To remove the blobs from the DOM, the attackers use URL.createObjectURL() to generate the blobs. Once this loader is executed, the attackers then call URL.revokeObjectURL(), which wipes any reference to the loader from the DOM.

Another aspect of blobs is that browsers typically do not display them when you open the JavaScript debugger; all you see is the ID, not the code it represents. While there are, of course, ways to view the code, it's another barrier that attackers used here to make it a little harder to analyze, and also make it that little bit harder for anyone reviewing the code to figure out what's going on, too.

We haven't seen blobs used as an evasion technique in Magecart attacks before, and most Content Security Policies aren't configured to prevent blobs from being loaded like this.

Stage 2: Smart Contract

This is another fascinating and novel aspect of the campaign: the attackers utilize blockchain smart contracts as a storage layer for their malware. The term "Etherhiding" has been used to describe storing malware on the blockchain; however, this is the first time we've seen a blockchain smart contract utilized in a Magecart attack.

This approach gives attackers an advantage - rather than hosting the skimmer on infrastructure that defenders could report and take down, instead, the second-stage queries a Binance Smart Chain (BSC) testnet contract to retrieve its payload. Because the blockchain is decentralised and immutable, defenders can't simply "take down" the source like they would with a compromised server. As long as the contract exists on the testnet, the malicious code remains publicly accessible and resilient against traditional disruption. It also means that attackers can update the smart contract at any time, and this new code will be loaded the next time a victim visits a compromised website.

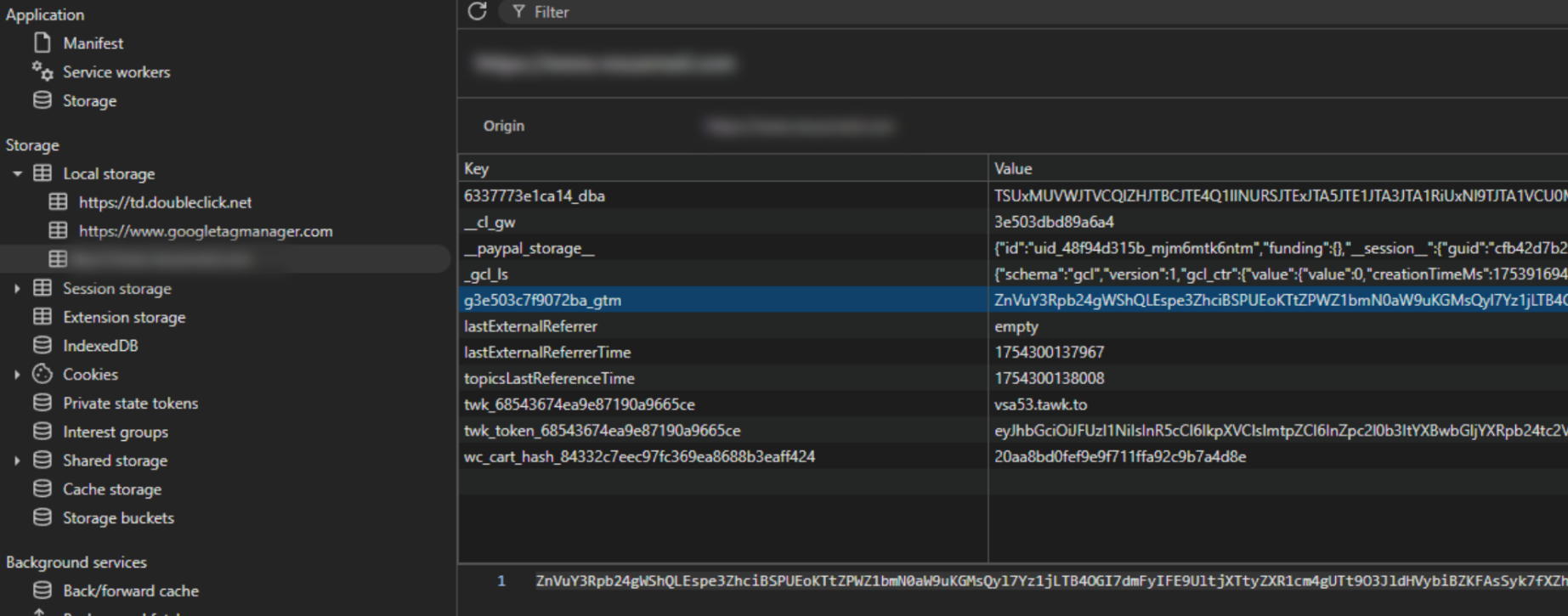

To hide the attack code in a smart contract, the data is encoded, and the loader decodes it and stashes it locally, in localStorage, and appends _gtm to the key to make it look at first glance like it's a Google Tag Manager-related key. Finally, this stage reassembles the data into another blob for execution.

As mentioned, this is a new development in web skimming. By hiding behind the persistence of a smart contract, attackers gain a level of censorship resistance and infrastructure redundancy that has not been seen before. Updating the skimmer is as simple as sending a new transaction to the contract, and there's almost nothing that defenders can do to erase the code once it's on-chain. This means that client-side security becomes even more critical because the delivery vector itself may be untouchable.

Stage 3: Websocket to communicate with the attacker's C2 infrastructure

The final stage of the attack is, again, a modern approach, but is more in keeping with what we usually see in this type of attack. The third-stage code connects to a command-and-control (C2) server via WebSockets. This provides attackers with a live communication channel through each victim's web browser. Once the smart contract payload is decoded and executed, the script opens a connection to domains like babymarket\.io, webawast\.xyz, kefersuc\.xyz or kezopersuc\.xyz, where it registers the infected session with a unique identifier.

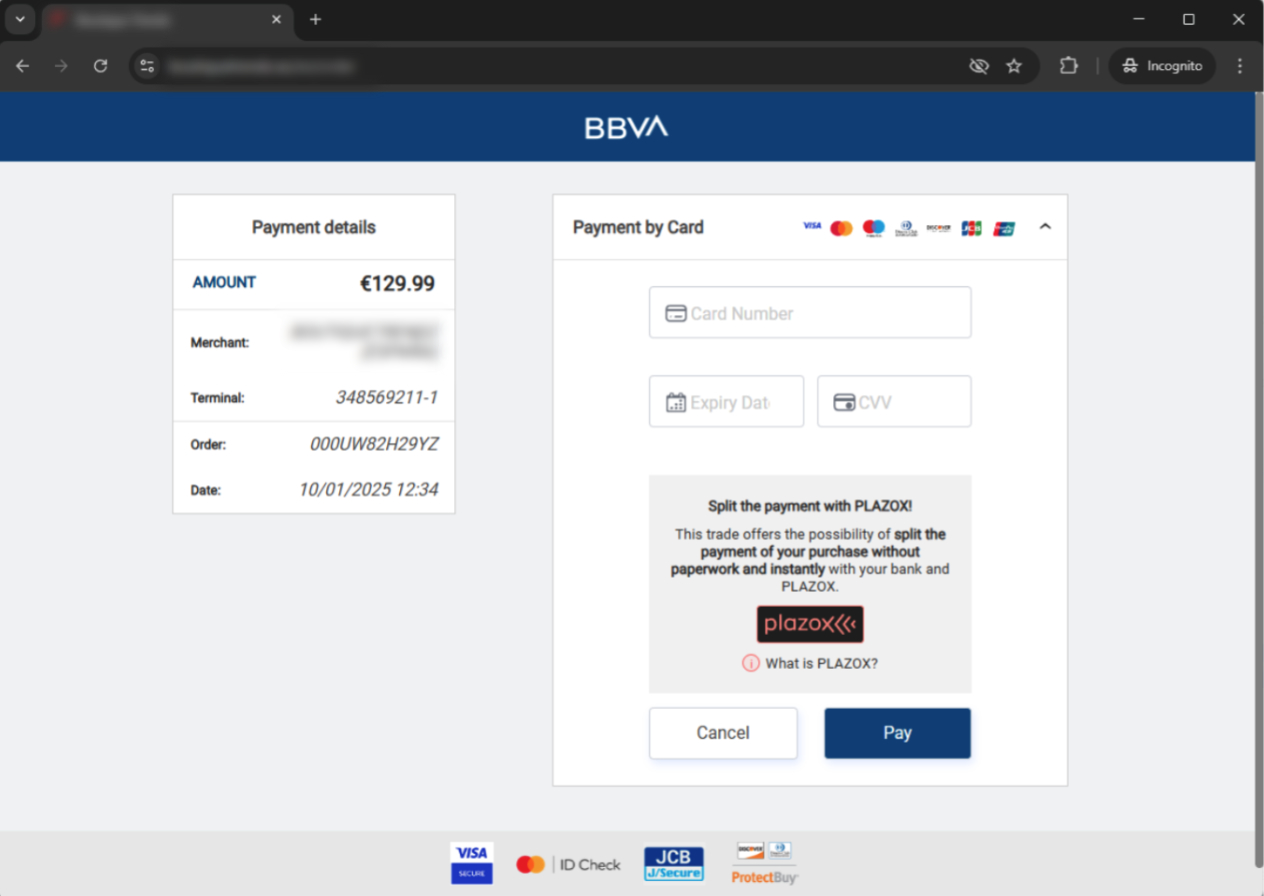

The attackers insert their skimming attack here - either by hiding the original payment iframe and replacing it with their own, or by inserting their own iframe that mimics the PSP for merchants utilizing a full redirect to the PSP. Again, though, the attackers go beyond the run-of-the-mill attacks, as in some cases they even display what appear to be fake 3DS and SMS prompts here too.

.jpg)

Fake 3DS Form

Interestingly, we observed the use of both silent skimming attacks and double-entry attacks in this campaign, which depended on the technology stack and PSP used by the compromised merchant website. For double-entry skimming attacks, the original payment iframe would be shown after the first "failed" transaction, where the attackers captured the payment details. Still, in the silent skimming attacks we saw both payment and customer cookie data being transmitted to the attacker's C2 infrastructure, immediately followed by a transaction attempt on the card, suggesting that the attackers were proxying the legitimate transaction.

Fake Payment Form

Fake Payment Form

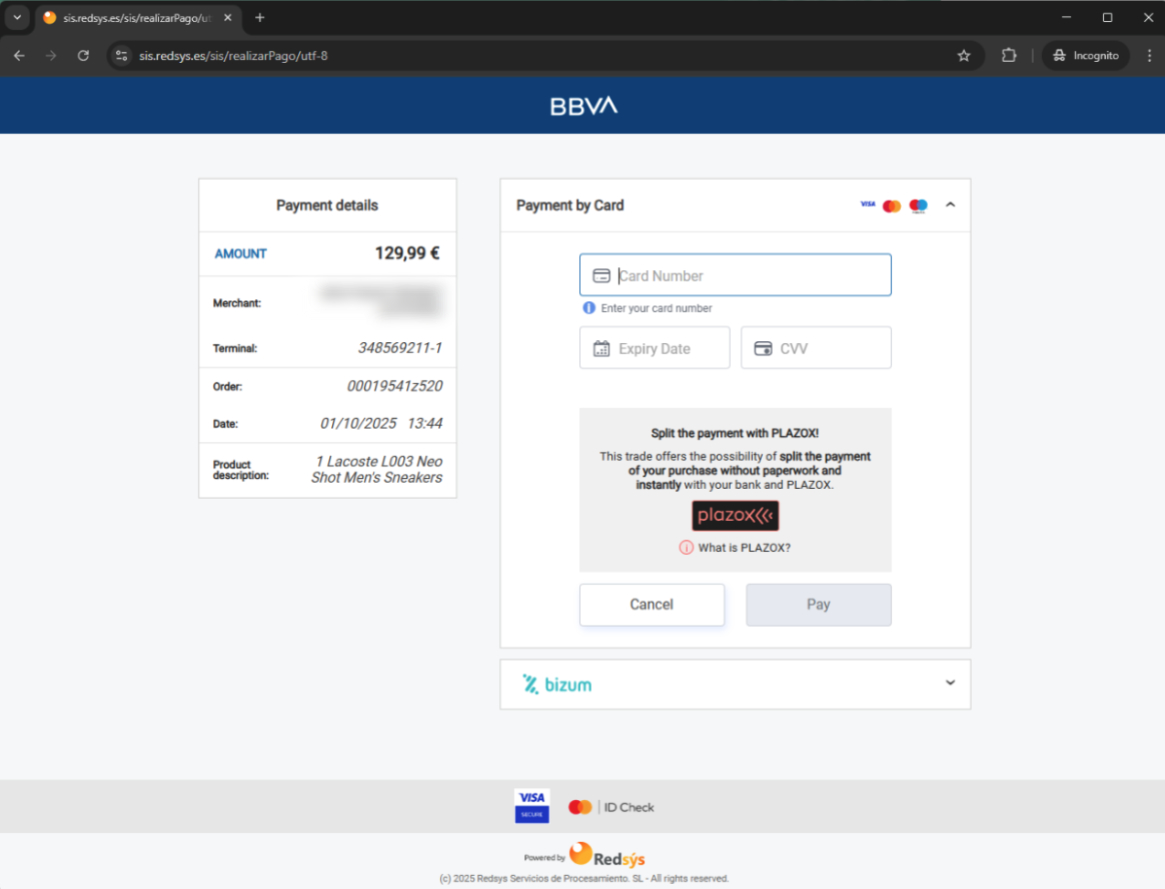

Legitimate Payment Form

Legitimate Payment Form

In this instance, the skimmer expects to find Stripe-related elements to replace, but we found several other payment service providers mentioned in other skimmer instances:

Bancard Payments

Bykea

CreditGUARD

Mercado Pago

Midtrans

Mollie

Monetico

Montonio

Payfast

Paypal

PayPlug

PayU

PhonePe

Pikpay

Razorpay

RedSys

Viva.com

Wompi

Using WebSockets instead of traditional HTTP beacons gives the attackers two significant advantages. First, it enables bi-directional communication, allowing the C2 to push fresh JavaScript payloads in real-time, rather than relying on static scripts. In fact, we discovered at least 37 different payload configurations being sent, depending on the origin of the request, the path, and other identifiers being sent from each site. Second, using web sockets means the traffic appears more like legitimate session traffic, which makes it easier to blend in with chat widgets, analytics, and other modern web features.

In an attempt to obfuscate what their attack script is doing, the attackers also include references to some legitimate URLs from several well-known PSPs within their script, again so that a casual reviewer might assume that this script is somehow involved in the legitimate payment flow.

.png)

An interesting benefit of attackers using a smart contract in the previous stage is that, if the attacker's C2 servers are disrupted, they only need to update the smart contract to point to their new C2 systems, allowing the attack to continue.

Smart Contract Updates

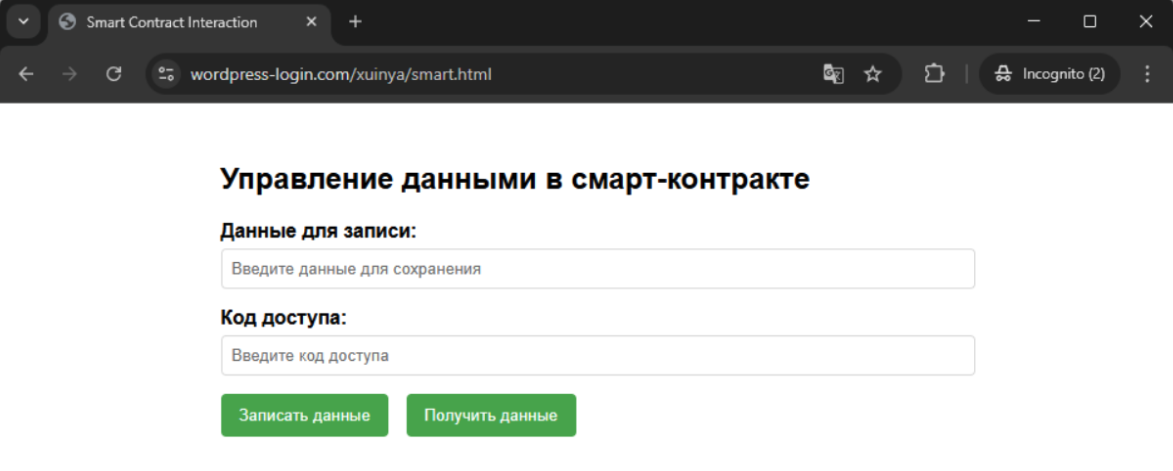

During our research, we also discovered infrastructure for managing smart contact updates. One was in use by this campaign and showed several updates, and another that appeared to be related, pointing to the same wallet, but unused at present.

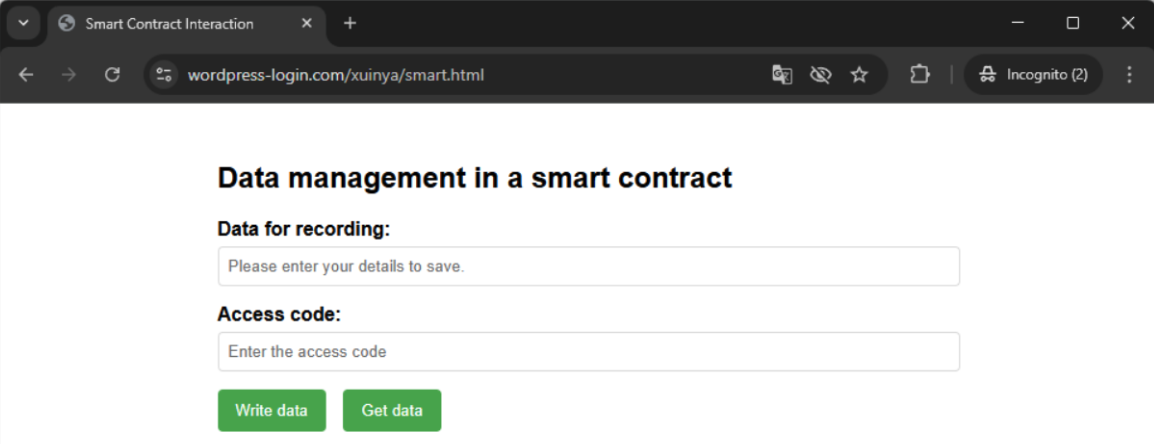

Original Smart Contract Data Management Page

Original Smart Contract Data Management Page

Translated Smart Contract Data Management Page

Translated Smart Contract Data Management Page

The page source code showed the mechanisms for updating the smart contracts. It relies on having the MetaMask extension installed on the web browser, which holds the attacker's private keys, and without which it's not possible to update the smart contract. However, by following the wallet address embedded in the page source code, we were able to discover additional C2 hosts used by the attackers, listed at the end of this post.

Impact

Jscrambler's security researchers discovered over 110 websites compromised to date, with the number of compromised sites increasing, and it is likely an underestimate, as many signs of compromise might only be visible to logged-in customers of these sites.

What can be done?

Once again, we see that using CSP and SRI alone is unlikely to prevent this type of attack on its own. Most of the victim websites had some CSP headers, but they were ineffective in preventing these attacks. Where entities use client-side protection technology, such as Jscrambler's Webpage Integrity, this type of attack would be detected by the out-of-the-box configuration. This is because Webpage Integrity monitors scripts' behaviors, and so the moment a blob or data source is accessed, it is automatically detected.

Compare this to what's necessary on an ongoing basis for a CSP/SRI configuration:

Ensure that your Content Security Policy (CSP) is as restrictive as possible, and explicitly block blob: and data: sources in script-src.

Ensure that your CSPs' connect-src parameter only includes required, known domains to detect rogue WebSocket connections.

Actively monitor and investigate CSP violations, and avoid CSP wildcards wherever possible, especially when referencing CDNs.

Ensure that security-impacting HTTP headers are being monitored, that alerts are received, and that these alerts are investigated promptly.

We also noticed that many of the affected merchants in this campaign were utilizing a full redirect to their PSP, but the attackers subverted that mechanism. PCI DSS doesn't include any controls to monitor these full redirect mechanisms, which we're now seeing attackers exploiting. Merchants, especially those using SAQ A, would be wise to proactively monitor their payment pages, even where a full redirect is used, to ensure that attacks like those described here are detected early.

Conclusion

This attack combines modern and new techniques to create a multi-faceted and hard-to-detect attack. Attackers continually find new ways to keep their exploit code available online, and the use of Blockchain smart contracts is a novel new approach that makes the attack code essentially impossible to take down.

Equally, attackers continue to obfuscate their code, such as making it appear to be part of Google Tag Manager or Stripe, in this case, and they continue to exploit legitimate browser features to make their attacks harder to detect.

Jscrambler also continues to observe that CSP and SRI are misconfigured or too lax on breached websites, and these technologies are simply insufficient on their own to prevent modern attacks. This is especially true when attackers exploit features like blob: URLs to circumvent more common detection mechanisms. Defenders need to use a layered approach, blending in client-side security to gain insights into the behaviour of all scripts across their websites.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs):

Smart Contract

Contract | Creation Date | Contract Creator |

0xb9a76d21df3c71209c42e601402709da650def7f | Jul-12-2025 10:01:48 PM UTC | 0xD016cA1e8Ec9FA90AB11498e98D5c0a7C6C85A04 |

0x41cab44cacded0af59e08d187efd8a3cbf2bd18a | Oct-15-2024 02:25:36 PM UTC | 0x5178a932D5b312801e02c43FD50399a88028b9D0 |

0x0967296defa0fd586c9ede5730380e2b059fab95 | Nov-08-2024 09:48:57 AM UTC | 0x5178a932D5b312801e02c43FD50399a88028b9D0 |

0xdde0e8f536abc0df8082b5df880e03d98180751a | Feb-13-2025 09:50:35 AM UTC | 0x62036ed878271b0c2E820c1AbF533d91DfF4448f |

0x3596a5d8fdd13763482de91a4ca74b7dbcbd98f9 | Jan-12-2025 09:19:23 AM UTC | 0xf62E8c14b894a8be0cC9501844f2C4B46140565C |

0xa3a94b59178a4b32a753be258892cc9c5b57c40e | Aug-13-2025 01:31:53 PM UTC | 0xf62E8c14b894a8be0cC9501844f2C4B46140565C |

0x885685dd99553c0c441ee37ba6ac93d21549b755 | Aug-13-2025 01:32:14 PM UTC | 0xf62E8c14b894a8be0cC9501844f2C4B46140565C |

0x0301ad41dbcbbeec4c03375ad136d69770fc6a81 | Aug-13-2025 01:58:53 PM UTC | 0xf62E8c14b894a8be0cC9501844f2C4B46140565C |

0x26b15226887d8afe94671f0551eea3ab16873be6 | Aug-13-2025 01:59:14 PM UTC | 0xf62E8c14b894a8be0cC9501844f2C4B46140565C |

0xc9233895f25b1135bd0bd352b4b97a7c7210f33b | Apr-02-2025 03:49:55 PM UTC | 0xdec39Acd463C68d8CF4086bcA538FEB44e21AA5B |

0xb5f454d3102f90c876e42bf8d077a16d24ba9d67 | Aug-13-2025 11:30:28 PM UTC | 0xb6B9D77b0723eaf356434C24EC5F79E25FC2a917 |

0x94d2c03f67790fbdeb875938433db0175b340717 | May-22-2025 09:34:23 AM UTC | 0x8d27f28819082AdB36850B1dcafB4F032154D9FA |

0x1c13cf158da35a385391db798752119a301d85b4 | Sep-02-2024 01:41:28 PM UTC | 0x5178a932D5b312801e02c43FD50399a88028b9D0 |

0xf62e8c14b894a8be0cc9501844f2c4b46140565c | Jan-09-2025 07:17:05 AM UTC | 0xc2F695613de0885dA3bdd18E8c317B9fAf7d4eba |

0xc19f7400850203f14014236dfab18b0821bfbf08 | Jan-09-2025 09:53:11 AM UTC | 0xf62E8c14b894a8be0cC9501844f2C4B46140565C |

0xdcd2aa8c6b34f940c073640ed8681d0505fbb1cb | Jan-09-2025 11:29:14 AM UTC | 0xf62E8c14b894a8be0cC9501844f2C4B46140565C |

0xc1b04be318fd252364cd247c2d544ecab3ebb6ef | Feb-11-2025 02:44:55 PM UTC | 0xf62E8c14b894a8be0cC9501844f2C4B46140565C |

0xe8aa199d3fbd8570b7b56b4e1bc9e384a58b2af6 | Sep-12-2025 07:29:22 AM UTC | 0xB32E5C1470b7CAc7e5D7f86C351B1e1765190936 |

0xfcb633fccea898c23e4a89a8f83f23941e75e034 | Oct-03-2025 09:08:18 AM UTC | 0xd14404519f9FD4113206f766c2992fD8AE7ECc10 |

0x574c15b6706317011fc7c9632b4b974c6d61a108 | Oct-05-2025 02:11:45 PM UTC | 0xd14404519f9FD4113206f766c2992fD8AE7ECc10 |

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs):

Domains

Domain | Registered On |

kezopersuc[.]xyz | 2025-03-28 |

kefersuc[.]xyz | 2025-03-07 |

keritysuc[.]xyz | 2025-03-07 |

suckerity[.]xyz | 2024-11-06 |

webawast[.]xyz | 2025-09-08 |

babymarket[.]io | 2025-05-08 |

wordpress-login[.]com | 2025-02-11 |

neshion[.]com | 2024-11-08 |

gagichls[.]top | 2025-08-05 |

test.gagichls[.]top | 2025-08-05 |

wsocket[.]store | 2025-04-02 |

woscket[.]store | 2025-09-12 |

elementatorprof[.]online | 2025-04-30 |

asd123qwe2[.]online | 2024-12-07 |

inspectlet[.]observer | 2025-08-21 |

websocket[.]click | 2025-03-06 |

insightanalytics[.]pro | 2025-05-22 |

wordpress-commerce[.]com | 2025-08-13 |

cdn[.]cdnjscookies[.]top | 2025-01-12 |

cn[.]ls1ks[.]xyz | 2024-02-07 |

cdn[.]iconstaff[.]top | 2024-02-28 |

gigacgetski[.]top | 2025-03-08 |

wooadminpro[.]com | 2025-09-16 |

References

Credit Card Skimmer Targeting WooCommerce Websites: Analysis and Mitigation

Persistent backdoors injected on Adobe Commerce via new CosmicSting attack

A beginner(s) guide to hunting web-based credit card skimmers

https://x.com/500mk500/status/1908166678514384926

https://x.com/sdcyberresearch/status/1866126596983115899

https://x.com/sdcyberresearch/status/1876212239570706724

https://x.com/sdcyberresearch/status/1954917161681457152

https://x.com/threatcat_ch/status/1895509272605409437

https://x.com/unmaskparasites/status/1950684339853037587

Jscrambler

The leader in client-side Web security. With Jscrambler, JavaScript applications become self-defensive and capable of detecting and blocking client-side attacks like Magecart.

View All ArticlesMust read next

The npm Chalk and Debug Attack Proves Again: The Web’s Trust Model is Broken

The web’s trust model is broken: on September 8th, 2025, Aikido reported a major supply chain attack affecting dozens of npm packages, including the hugely popular chalk and debug. In total, the...

September 10, 2025 | By Pedro Fortuna | 17 min read

Stealing Seconds: Web Skimmer Compromises Casio UK and Growing Number of Websites

Jscrambler just uncovered a new batch of web skimmer infections affecting multiple websites, including casio.co.uk. So far, 17 victim websites are confirmed, though this number will likely increase...

January 31, 2025 | By Pedro Fortuna | 10 min read